BEYOND THE WILDERNESS

Ansel Adams in 1940s Los Angeles

January 15 - March 28, 2026

Opening Reception: January 15, 4-6pm. Reception and admission are free and open to the public.

Ansel Adams is a household name. As perhaps the single most widely recognized photographer in the world, visitors to Beyond the Wilderness may arrive with a specific notion of who he was and what he photographed. This exhibition, however, may be surprising, as it does not feature the expected images you would associate with Ansel Adams – the photographer, environmentalist, and creator of the Zone System of photography.

Many of the featured works in the exhibition come from the collection of the Los Angeles County Public Library, to which Adams offered a series of 217 negatives portraying 1940s Los Angeles in the lead-up to World War II. Adams shot the images on assignment for Fortune magazine to document the lives of workers in Los Angeles’ booming aviation industry driven by aircraft company giants Douglas, Lockheed, and Northrop. These unique images document the life and times of the factory workers and of the city itself in late 1940 and early 1941, just prior to the entrance of the United States into World War II. The images give us a glimpse into what life was like in Los Angeles at this time: revealing how people dressed, where and what they ate, the unique architectural monuments of the city, and the vast number of open spaces and oil wells that once inhabited the valley, as well as Adams’ eye as the photographer, his proclivity for experimentation, and even his sense of humor. Given our proximity to Los Angeles, some of these locales are familiar, but many are long gone, torn down and replaced in the name of progress. In some instances the original structures still survive, but the facades have changed and only glimpses of 1940s Los Angeles remain today.

Fortune used only a small selection of Adams' journalistic images in a story titled “City of the Angels” in their March 1941 issue, and the remaining images languished in Adams’ personal files for more than 20 years until they were offered to the city of Los Angeles upon his move to Carmel, California in 1962. In Adams' accompanying letter, he clearly didn’t think highly of these images; shot in overcast weather and far outside of the typical subject matter that he truly championed, he felt they were not his best work. In fact, he suggested that they find their way to the “incinerator” if there was no use for them in the library’s collection. Despite this, Adams recognized their historical value, which tells the tale of a pivotal moment in American history and documents life in a city that was rapidly expanding into what is today one of the largest in the country. Unlike many of Adams’ nature images, these images offer us a raw and untouched glimpse into his eye for setting up and framing a photograph, instinct for finding rhythm and structure in everyday scenes, and willingness to experiment beyond the boundaries of his established aesthetic.

WATCH: Special Gallery Lecture with Dennis Doordan, PhD: "Looking at Ansel Adams Looking at L.A."

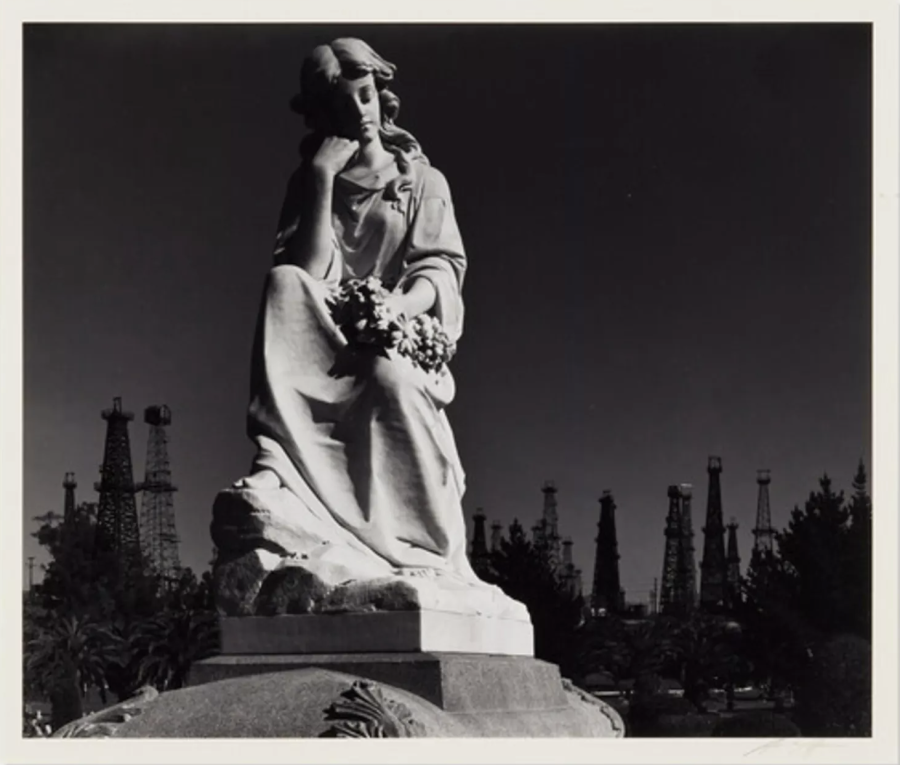

Of all the images Adams took during this assignment, only a single photograph was personally printed and used by Adams as part of his published oeuvre: Cemetery Statue and Oil Derricks, Long Beach, California, which comes from our permanent collection.

It is impossible to talk about Ansel Adams without also addressing his love of nature, his pioneering efforts toward conservation and stewarding environmentalism, and his moral convictions regarding the United States’ internment of Japanese Americans. One of Adams’ most famous photographs, Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada, From Lone Pine, California, also included in the exhibition, was taken shortly after his assignment for Fortune. In December of 1941, America entered World War II with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February of 1942, authorizing the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans on U.S. soil.

One of ten concentration camps established by the United States government happened to be placed in Adams' own backyard, in the Owens Valley at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Adams petitioned the U.S. government to photograph the lives of Japanese Americans imprisoned at Manzanar and was granted access. Between 1943 and 1944, he made several trips to Manzanar at his own expense to photograph the people, the community, and the landscape in and around the camp. The resulting images were published and exhibited in 1944 in a book titled Born Free and Equal: Photographs of the Loyal Japanese-Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center, Inyo County, California. Despite Adams’ efforts and intent, the work was not well received by an audience who mostly rejected sympathetic portrayals of Japanese Americans due predominantly to wartime fears and prejudice. In Adams’ own words, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and despair by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment.”

Like Winter Sunrise, most of Adams’ iconic images of nature are complex to print in the darkroom, due in part to his technical innovation he called the Zone System. Rather than guessing on a camera’s exposure setting, Adams developed a process of exposing a negative to retain detail in the darkest areas and manually lightening areas of the negative in the darkroom to have better control of the printed result. Adams’ revolutionary approach was to “expose for the shadows, develop for the highlights,” meaning that much of the tonal quality he achieved in his images came from time spent manipulating the image in the darkroom during the printing process. It was Adams' way of experimenting, controlling, and fulfilling his artistic vision of each exposure.

Viewed together, the photographs in this exhibition remind us that Ansel Adams was far more than the maker of pristine wilderness icons. He was an artist attentive to the world as it was, and how it ought to be. Whether documenting factory workers on the brink of war, confronting the injustice of incarceration at Manzanar, or shaping luminous visions of the Sierra, Adams used his camera to advocate for dignity, clarity, and stewardship. This exhibition invites us to see Adams anew — not solely as a master technician of the Zone System or a champion of the American landscape, but as a witness to history and a moral voice whose images still ask us to look closely, think critically, and care deeply for both people and place.