We live in a highly charged political climate, and the need for well-informed, discerning political engagement is acute. But all too often instead of information we get sound bites, instead of analysis of issues we get coverage of campaign horse races, instead of deliberation we get debates, instead of critique we get attack. The fairness of our sources of information is doubted in every direction. Analyses of issues are everywhere assumed to be tainted by political prejudice.

There is nothing new or surprising about this political climate. But it does present a serious challenge to a central goal of a liberal arts education: to help students become engaged and thoughtful participants in our political life. Some students turn off, regarding the political realm as a swamp of self-interest masquerading as public good. Others engage passionately, but at times simplistically, carving the political landscape into realms of good and evil, and failing to bring their critical skills to the claims of friend and foe alike.

The task of "Learning in a Time of Politics" was to learn from each other how best to help students become critical, informed, and engaged participants in our shared political life. We considered classroom strategies and extra curricular programs as well as broader questions of campus climate and how academic institutions are themselves political agents.

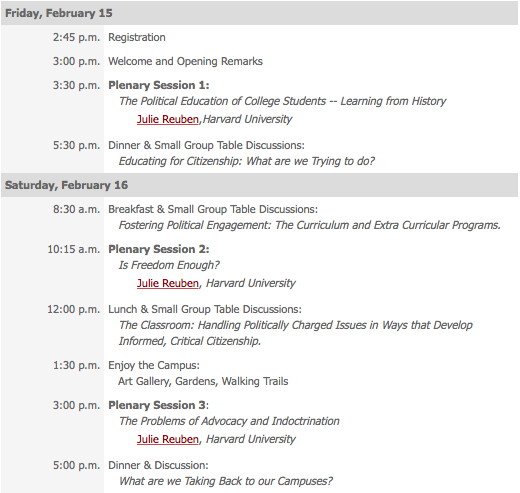

Harvard historian of education Julie Reuben served as catalyst for our conversations. Professor Reuben has done outstanding work in the relationship between educational institutions and American political life. Her contributions offered us concrete examples of efforts to educate for citizenship: what has motivated those efforts, what assumptions and values have undergirded them, and what their results have been. In addition to the three plenary sessions led by Professor Reuben, we also enjoyed ample opportunity for discussions on campus-wide programs and classroom strategies that foster fruitful political engagement.

Professor Julie Reuben -- Harvard Graduate School of Education

Julie Reuben is a historian interested in the role of education in American society and culture. Her teaching and research address broad questions about the purposes of education, the relation between educational institutions and political and social concerns, and the forces that shape educational change. She is the author of TheMaking of the Modern University: Intellectual Transformation and the Marginalization of Morality. This prize winning book examines the relation between changing conceptions of knowledge, standards of scholarship, and the position of religion and morality in the American university during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition, she has written a number of articles related to campus activism, access to higher education, curriculum changes, and citizenship education in the public schools.

Reuben is a Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She has been selected as a Fellow for the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences and received a Major Grant from the Spencer Foundation. She received her B.A. in history from Brandeis University, and her M.A. and Ph.D. in history from Stanford University.

The following are recordings of lectures given by Harvard historian of education, Julie Reuben at the Eighth Annual Conversation on the Liberal Arts. These lectures address the topic "Learning in a Time of Politics: Liberal Arts Education and Political Engagement."

|

Keynote Address #1 -- History of Political Engagement in American Colleges and Universities Keynote Address #2 -- Problems of Indoctrination and Advocacy Keynote Address #3 -- How do we get Advocacy without Indoctrination? |

Professor Lisa DeBoer contributed:

- I kept thinking about the relationship between $$ and institutional goals. As Julie recounted it, in the 1960s there were two models in the offing for how to accommodate student demands for change, and political education. The one (making area studies look more like interdisciplinary) had funding from the Ford Foundation, the more radical version (including embodied knowledge, including more than academics in the learning community, identity studies) did not. Guess which one succeeded? For us, do we have donors and sources of funding that will step up to the plate, if we decide to define our mission in terms that are a bit outside of academic norms?

- I was struck by the relationship between notions of "academic freedom" as they developed over the course of the first half of the century, and loss of an educational core (in which political education was seen to reside) in the second half. To quote two different poet/lyricists: "Freedom" is just another name for "nothing left to lose" and "What you thought was freedom is just greed." There's been some work done on academic freedom at religious institutions, but it seems to me Westmont could make more use of this for our own self-understanding, as well as for our self-representation.

- We didn't really resolve at all the pedagogical dilemmas of representing a position. Nor did we explore at any depth the relationship between experimentation/applied learning to political education. That's where the practical payoff probably is.

Angela D'Amour (Director of Campus Life, Westmont) contributed:

Promising Idea:

- In the same way that science and language courses have labs for hands on experience, so too should all humanities and social science courses have lab elements that move students from head knowledge into applied knowledge where they have an opportunity to see and practice what they're learning in the classroom. Political science courses should be attending city council meetings, meeting congress people and advocating for issues that are important to them. Art history students should be visiting local museums, speaking with local artists and offering art history instruction to elementary classrooms. These practices would revolutionize a liberal arts education.

Remaining Question:

- The catch 22 for the liberal arts institution's aim to educate students for civic involvement is that it is only so far as it involves non-partisan support. It's tricky when we're trying to develop passion in students for democratic processes but only so far as they can never truly align with a particular political candidate. We must retain our neutrality, but it's difficult to develop true interest and passion with neutrality.

Chris Callaway (Philosophy, Saint Joesph's College of Maine) contributed:

- What sort of normative assumptions about democracy and citizenship lie behind various civic educational initiatives, or behind the idea of civic education itself? For example, is it premised on a claim about the value of civic engagement for living well (a la civic republicanism) or on a view of political obligation? If so, is that a problem?

- What reasons are there for thinking that civic formation is properly part of the mission of a college or university? How consistent is civic formation with what is clearly part of higher education (i.e., intellectual formation)?

- If higher education is supposed to provide a model of civic participation, is it a problem that most faculties skew strongly toward liberal political positions? Even if no department intends to hire only “liberal†professors, is it a problem if such is the end result? I suppose a different way of putting this question is: Can colleges and universities effectively model civic engagement without also modeling political pluralism? That question obviously cuts both ways; it challenges faculties that, for one reason or another, tend to be conservative.