Remembering My Father: Provost Mark Sargent

By

Westmont

My father—Joseph Linden Sargent—passed away almost twelve years ago, yet there’s still hardly a Father’s Day that goes by when I don’t remind myself to call him. That thought usually hits me about dusk, or when I look at one of his watercolors on our walls. He died on his anniversary, nearly two years after my mother’s passing. Fifty-seven years earlier, in a small, private wedding, my mother had marched to the altar down a narrow stairwell in my father’s childhood home. Dad loved telling us about growing up in Long Beach: the earthquake that left many in tents, the roller coaster at the Pike, the Brethren church at “Fifth and Cherry” where he and Mom met. He wanted his three boys to love the beach as much as he did, so we spent many evenings building sand forts at Huntington and climbing over rocks to wait for sunsets at Laguna. The magic hour, in our family, was always twilight.

My father—Joseph Linden Sargent—passed away almost twelve years ago, yet there’s still hardly a Father’s Day that goes by when I don’t remind myself to call him. That thought usually hits me about dusk, or when I look at one of his watercolors on our walls. He died on his anniversary, nearly two years after my mother’s passing. Fifty-seven years earlier, in a small, private wedding, my mother had marched to the altar down a narrow stairwell in my father’s childhood home. Dad loved telling us about growing up in Long Beach: the earthquake that left many in tents, the roller coaster at the Pike, the Brethren church at “Fifth and Cherry” where he and Mom met. He wanted his three boys to love the beach as much as he did, so we spent many evenings building sand forts at Huntington and climbing over rocks to wait for sunsets at Laguna. The magic hour, in our family, was always twilight.

In time, my father became a public school teacher and administrator, but he really had a tradesman’s heart. He routinely urged me to season my love of the liberal arts with some blue-collar wisdom. From his father, he learned to install ceramic tile, and he set bullnose caps and leveled grout joints with a surgeon’s touch. He taught himself to paint, and won awards, both as a young man and a retiree. He was a hurdler in high school, and a walk-on coach during his teaching years. His sports heroes were usually college stars, including a long-jump champion from UCLA named Jackie Robinson. He loved watching the Rose Bowl, especially late in the third quarter when the alpenglow took over the Pasadena hills.

Dad enjoyed old Westerns and opera—Gene Autry, Gilbert and Sullivan, and “Madame Butterfly.” I always thought that last one made him think of my Uncle Jim, his only sibling, a soldier who befriended many Japanese families during the postwar occupation. After my father's passing, we found a leather shaving kit filled with dozens of letters and cards he had exchanged with his brother during the war more than sixty years earlier. Those letters revealed no secrets, only loyalty.

Dad enjoyed old Westerns and opera—Gene Autry, Gilbert and Sullivan, and “Madame Butterfly.” I always thought that last one made him think of my Uncle Jim, his only sibling, a soldier who befriended many Japanese families during the postwar occupation. After my father's passing, we found a leather shaving kit filled with dozens of letters and cards he had exchanged with his brother during the war more than sixty years earlier. Those letters revealed no secrets, only loyalty.

Dad always kept lots of wondrous and cast-off things. Our home was a storehouse for invention: antique tile, stained glass, driftwood, scraps of lumber. Refrigerator boxes became backyard castles. Surveyor stakes became ships launched in the back bay of Costa Mesa. Wooden glass crates got disassembled to make goalposts for the family football fields, sometimes with goal lines of left-over lime or grout. Nothing purchased ever matched the wonder of things found and remade. He saved scores of maps, turned some into puzzles, and put up shelves to hold decades of Life magazines and National Geographics. It’s no surprise that his kids learned to love history and home repair: we are all heirs of the curiosity shop that was Dad’s garage.

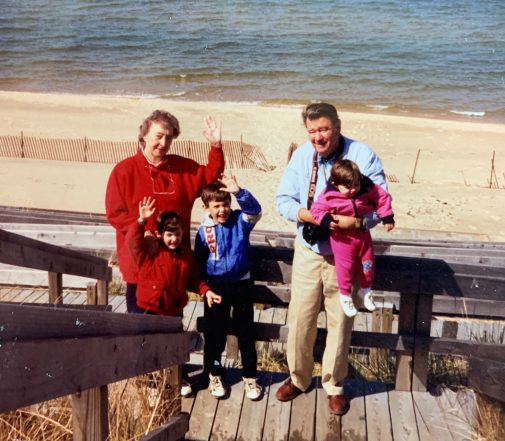

By the time his nine grandchildren had arrived, Dad’s creativity had shifted to his gardens—the mosaic basins, the roses and poinsettias, the jade plants and cannas, and the many geraniums, often sprouts from previous cuttings. But he never banned the whiffle ball or badminton games that threatened the flowers. He wanted his grandchildren to run free.

Dad graduated from Long Beach State and Chapman College, yet he spoke most often about his three years as a seminarian at Grace in Indiana. Many of his life-long friendships were forged there. He loved pulling out Strong’s Concordance or discussing favorite commentaries, especially when we used them as weights for pressing leaves or gluing posters for Sunday School. Like Mom, he always believed that the heart of a church was its Sunday School, a network of volunteers. Between them, Dad and Mom did several stints as Sunday School superintendents, and Dad invented a time machine, a rocket, and all kinds of contraptions to enliven Vacation Bible Schools. He was nostalgic about the early years of Westminster Brethren Church, especially since he and several parishioners literally built the place—laying linoleum, hanging drywall, and designing the sanctuary lights and stained-glass window. I have always assumed that church planting meant learning to pour concrete.

Seminary, in the original plan, was preparation for Brazil, and even though that journey was rerouted Dad brought a missionary's spirit to his work in the public schools. As a principal, he revived a high school on a juvenile detention ranch; teenage men, sentenced to labor in the hills, began to earn diplomas. In his final post, he launched language and citizenship classes for immigrants, particularly after our hometown of Garden Grove became a center for refugees from the Vietnam War. He was gregarious and unpretentious, as eager to speak with the custodian as the superintendent. He was at his best when he walked the campus to talk with his teachers.

I owe my life in education and in the church to my father and mother. Those were realms of considerable joy for them, and some sorrow. Dad encountered Christians who distrusted his art or his ardor for the public schools, and he grieved a couple church splits. A few prominent John Birchers opposed his work educating felons. But he was never the ideologue. His faith was about finding what was broken or discarded, and making it new.

Filed under

Academics, Alumni, Faculty and Staff, Featured, Press Releases