A Human Approach to AI: Understanding Its Promises and Perils

by Guang Song, Professor of Computer Science, and Mike Ryu, Assistant Professor of Computer Science Adapted from a Westmont Downtown talk in March 2025.

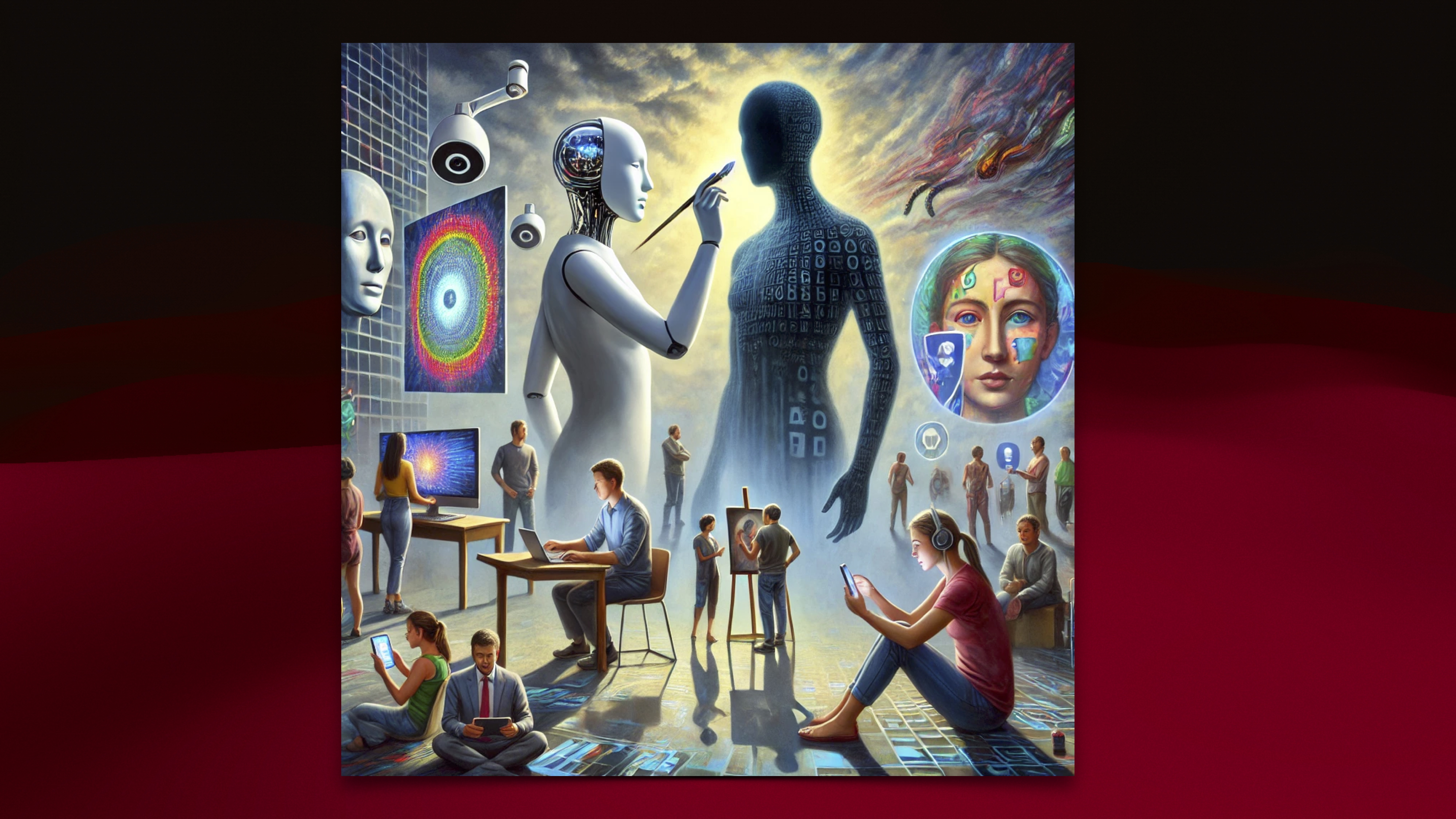

How can we best engage ethically with artificial intelligence (AI) and its accelerating influence? We seek to establish a framework for critically evaluating its impact on human lives — as both a tool of empowerment for extraordinary achievements and a force that risks undermining human dignity through its underlying biases and resulting harms. Exploring AI’s deep roots in the 75-year history of computing will help demystify the mechanisms behind its seemingly incomprehensible abilities as we examine key breakthroughs that have fueled the explosion of generative AI innovations.

What is AI? Many definitions exist, beginning in 1955 with “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines.” IBM refers to “technology that enables computers and machines to simulate human learning, comprehension, problem solving, decision making, creativity and autonomy.”

In 2018, the Department of Defense explained AI as “the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence … whether digitally or as the smart software behind autonomous physical systems.” The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers says, “Regardless of the exact definition, artificial intelligence involves computational technologies that are inspired by — but typically operate differently from — the way people and other biological organisms sense, learn, reason, and take action.”

In fact, no accurate, mathematical definition of AI exists, although all AI happens on a computer. When referring to AI, most people mean generative AI (GenAI), which creates new content, such as texts, images, audios and code, by learning from existing data. In contrast, narrow AI involves simple actions such as facial recognition and line-cross detection when driving. GenAI, such as ChatGPT, generates — or more accurately — predicts what comes next.

In fact, no accurate, mathematical definition of AI exists, although all AI happens on a computer.

The speed of GenAI, four hundred quintillion operations per second, gives it intelligence. How does it compare to the brain? A working brain receives neurons and passes them on to a neural network, having learned to make appropriate connections. GenAI uses mathematical formulas to represent what neurons might do in an artificial network. As GenAI “learns,” it “weighs” factors involved in making accurate connections and predicting what comes next. For example, it learns what comes after, “O say, can you . . .”

Imparted intelligence represents a better name for AI. A computer is a circuit, doing nothing but running the current, and a computer program is a sequence of instructions. AI “knows” nothing about what it’s doing, but merely runs the computer program its human designers give it. Everything AI has is imparted.

So what makes it so powerful? It exceeds our brain power in some areas as it possesses a much larger memory, has access to a much larger set of information and data and features a much higher processing speed.

As a tool, computing extends the reach of our mind and feet. A story in the Atlantic observed, “Without the computers on board the Apollo spacecraft, there would have been no moon landing, no triumphant first step, no high-water mark for human space travel. A pilot could never have navigated the way to the moon, as if a spaceship were simply a more powerful airplane. The calculations required to make in-flight adjustments and the complexity of the thrust controls outstripped human capacities.” Humans needed a computer to accomplish these tasks.

We find AI useful because of how much inference it can do. The collective human knowledge of the past centuries resembles a huge oil reserve, with much of it hidden. AI (inference) reveals some of what exists below the surface, bringing out something that we know but were unable to articulate.

GenAI solves many problems. Consider its application to computational structural biology, which has long sought to predict protein structures. In 2021, a team of researchers designed a novel AI architecture (Alphafold 2) and used it to solve one of the biggest long-standing problems in structural biology: the protein folding problem. This success resulted from decades of hard work and the collective knowledge of many scientists. AI took the final step to a solution, and this work received the 2024 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

I (Guang Song) once wanted to convert a computer program from one language to another (Java to Python) to give students some examples from Java. It would take hours of work, so I asked ChatGPT for help, but it provided code that didn’t work. It made subtle mistakes. Fortunately, I knew Python very well, so I could quickly see the mistakes and fix them. To use this GenAI effectively, I had to be in the loop with enough knowledge to spot the problem. Someone unfamiliar with Python would have been stuck.

I find ChatGPT useful in doing research in computational biology and ask it to summarize some things for me. But I need to know the field well enough to ask the right questions (prompts); that’s a major part of problem-solving. And I always take the response with a grain of doubt. If necessary, I’ll research what the literature says to find the answer myself.

This brings us to the limitations of AI, which knows nothing about what it’s doing. AI merely runs the computer program from its human designer, who imparts everything AI has. And what we can impart is limited.

For example, we can’t impart what God gives us, such as consciousness, creativity, inspiration, love, imagination, etc. God breathes into us from above. These passages from the Psalms explain our human limitations.“He who planted the ear, does he not hear? He who formed the eye, does he not see? He who disciplines the nations, does he not rebuke? He who teaches man knowledge — the Lord — knows the thoughts of man, that they are but a breath” (Psalm 94:9-11, ESV). “Great is the Lord, and greatly to be praised, and his greatness is unsearchable” (Psalm145:3, ESV).

AI works solely on existing knowledge and gives us only what can be inferred; it’s unable to provide anything like Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence equation (E=mc2). It’s probabilistic by nature rather than accurate. While AI can perform a huge amount of preliminary work for you, you need to know the subject well enough to check its work. In fact, AI serves best as a secretary.

While AI can perform a huge amount of preliminary work for you, you need to know the subject well enough to check its work. In fact, AI serves best as a secretary.

As a result, we have no need to feel threatened — just as we’re not worried about dump trucks! AI is only a servant, a tool. In the future, AI or robots may do some of our work, which is OK. We’ll find something better to do.

But we need to engage AI with caution and a culture shift. A human-first culture can lead us to a brighter future by preventing us from abdicating human dignity. Let the human heart guide our actions. AI can’t overtake our lives if we don’t let it. And this culture change starts with me and you.

Guang Song taught computer science for 16 years at Iowa State University before joining the Westmont computer science department in 2022. He earned a doctorate at Texas A&M University and focuses his research on computational biology, exploring how proteins move, studying their molecular mechanical systems and classifying their various shapes. He has received a National Science Foundation Career award. His interdisciplinary research involves multiple disciplines, such as math, computer science, biology and physics.

Mike Ryu earned a Bachelor of Science in software engineering and a Master of Science in computer science from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo before working in the San Francisco Bay Area as a software engineer, agile coach and engineering manager. He came to Westmont in 2023 to teach computer science and mathematics and works as the director of engineering for the mobile and AI development teams at Westmont’s Center for Applied Technology (CATLab).

Further Reading

“The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power,” Shoshana Zuboff (2018). Surveillance capitalism unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data.

“The AI Mirror: How to Reclaim our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking,” Shannon Valor (2024). For many, technology offers hopes for the future. Yet rather than open new futures, today’s powerful AI technologies reproduce the past. This results in a flawed mirror, reflecting the same errors, biases and failures of wisdom that we strive to escape.